“If this is coffee, please bring me some tea. But if this is tea, please bring me some coffee”

So it seems not everything has changed since Lincoln’s days. Ordering a coffee in the 21st Century is still something of a lottery: you may get notes of jasmine, red fruits and dark chocolate. Or you may get notes of mold, rubber and straw.

Looking at the production chain, it’s perhaps a miracle there isn’t more bad coffee. The whole thing can go wrong at multiple points, from harvesting the beans incorrectly to allowing your brewed coffee to stew for several hours.

Colombia has carved out a reputation for good coffee, partly because it has reduced the amount of defective green coffee that leaves its shores, destined for your local roaster and a creamy cappuccino.

One man who deserves lots of credit for this is Edgar Moreno, Director of Quality at Colombia’s National Federation of Coffee Growers.

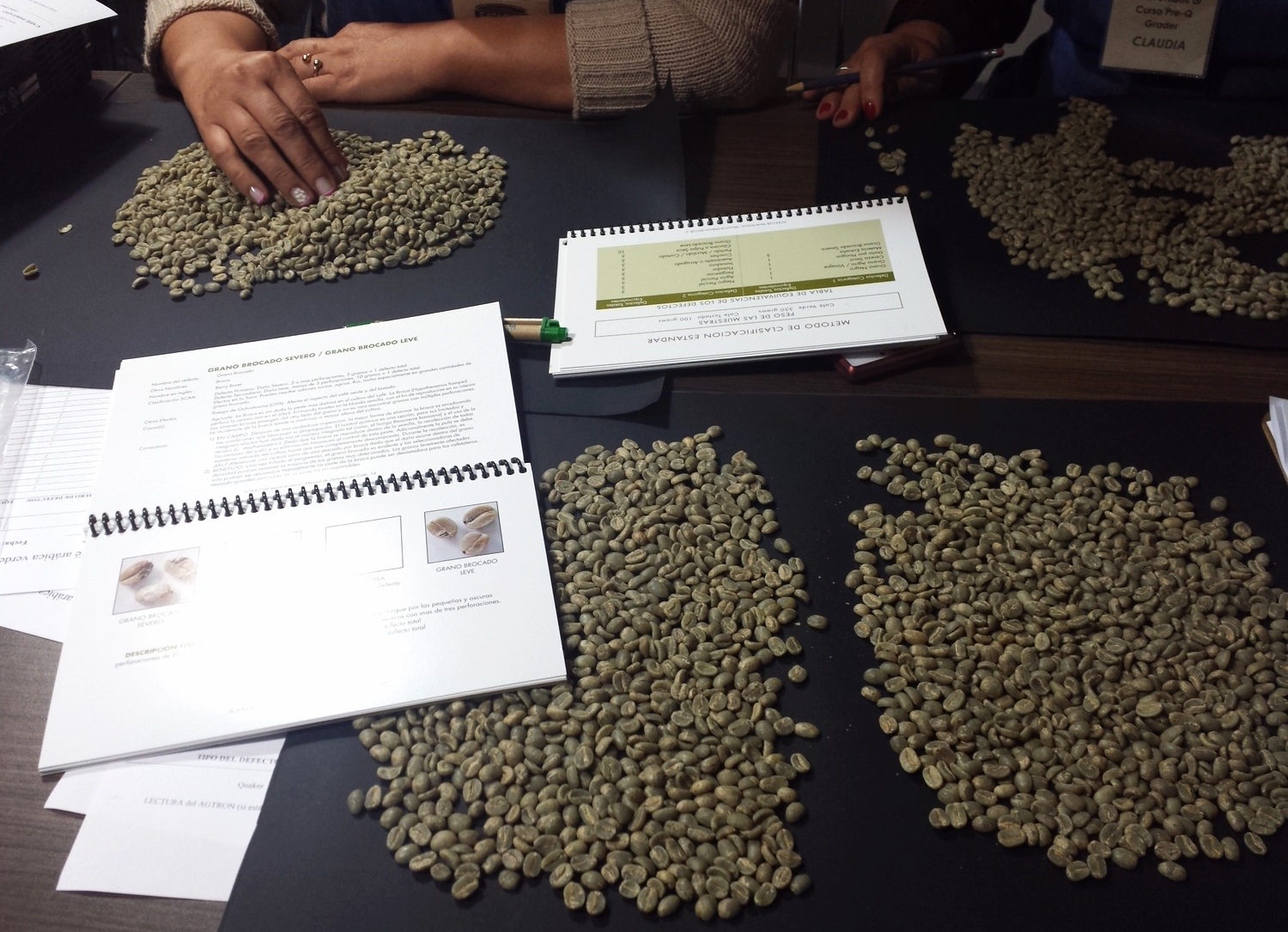

The federation has teams of inspectors in the ports of Buenaventura, Cartagena and Santa Marta. If they spot beans that have been attacked by fungi, beetles or contain twigs, they don’t make the ferry.

Suspect batches are sent to Edgar in Bogota where he dons his laboratory coat, roasts and cups the coffee using a standardize technique of sniffing, sipping and spitting.

Sour and moldy flavors are a sure sign of under-ripe or over-ripe beans, fungal attacks or poor processing.

The process isn’t always popular with Colombian farmers who are called by the inspectors to collect their crop if it doesn’t meet the grade. Apart from the inconvenience, they are then forced to sell it on the domestic market at lower prices (yes, the best stuff leaves).

But it has helped to keep Colombia synonymous with quality in overseas markets.

Specialty coffee has especially low thresholds for the amount of damaged beans that are allowed. Thanks to Colombia’s self-imposed export rules it is the world’s largest supplier of specialty coffee.